Few Vaquita Remain as Efforts Fail to Slow Decline

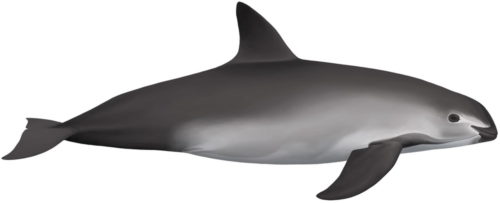

A recent report published by the International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita (CIRVA) paints an alarming picture of the ongoing struggle to save the world’s smallest whale from extinction.

But the report also emphasizes that there is still a chance to save the species. The remaining vaquita inhabit an area of just 24 x 12 km ─ small enough to police effectively, if the government were to enforce the law. That does not sound like a difficult undertaking, but news reports of ever larger seizures of swim bladders indicate that the illegal totoaba fishery is actually growing despite a strict fishing ban and the presence of the Mexican navy.

Illegal Totoaba Fishery Deadly and Highly Profitable

For decades, scientists have known of the decline of the vaquita and pointed to accidental entanglement in gillnet fisheries as the cause. The Mexican government responded with a long list of measures, but none were potent enough to stop or even slow the decline. In recent years, illegal fishing for the totoaba, a once abundant large fish, has proven lethal for the totoaba as much as it has for the vaquita ─ they are now both facing extinction.

The poachers fishing for totoaba are emboldened by a lack of enforcement. According to reports, they carry out their illegal activities in broad daylight, in what can only be described as a well-organized criminal operation, benefiting primarily the cartels that fund it. Law enforcement appears powerless in the face of alleged corruption and officials’ ties to organized crime.

A risky last-ditch effort to capture some of the remaining vaquita to keep them safe from poachers and their gillnets ended in the fall of 2017 when a female vaquita died following capture and release. Since then, all efforts have concentrated on the removal of gillnets, still the only serious threat to the vaquita and the totoaba.

International and local NGOs like the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society and the La Paz Whale Museum have been working tirelessly for years to remove mostly derelict and abandoned fishing gear. But with so few vaquita remaining, all it takes are a few nets to wipe out the entire population. And new nets appear every day, while vaquita continue to drown.

Resentment, Violence and Denial

When it became apparent that legal fisheries were being used as a cover for poaching activity, the Mexican government responded by declaring a total ban on gillnet fishing for the entire known range of the vaquita. The ban implemented a key recommendation by CIRVA, which had called for a complete stop to all gillnet fishing.

At the same time, NGOs around the world began to lobby for a boycott of shrimp imported from Mexico to put pressure on the Mexican government. In 2018, a US court upheld an import ban on seafood caught with gillnets in Mexico’s Upper Gulf of California.

Sunshine Rodriguez Peña, an outspoken and controversial leader of the fishermen in San Felipe, blames the government for the violence. In live video posts on Facebook and in frequent media interviews, he regularly rallies his followers against what he recently called a “policy of repression and persecution”.

The government, as their rationale for a total gillnet ban, argues that the small-meshed nets used in other fisheries also pose a risk to the vaquita. They have evidence from the scientific community to back it up: Worldwide, more than 300,000 whales, porpoises and dolphins are believed to get entangled in fishing nets of all sizes every year.

But Rodriguez, who has himself been linked to organized crime (an allegation he vehemently denies), does not believe the government’s arguments. In fact, he is convinced that fishermen are being falsely blamed for the demise of the vaquita, and he gets creative when asked what was killing the animals instead. In an interview in 2016, he blamed everything from red tides to shark predation ─ despite animals washed ashore clearly showing the telltale marks of net entanglement.

Pollution and the Colorado River

Rodriguez is not alone in his denial. Undermining the support for the conservation efforts and bolstering the opposition against an end to gillnet fishing in the Sea of Cortez are various ideas that, when examined more closely, resemble conspiracy theories more than they are based in fact. These false narratives shore up resentment directed at environmentalists and the conservation mission among the fishermen and within their communities.

More about the vaquita

Related Articles

Knowledge Base

A study found that productivity in the Northern Gulf had not been impacted. The Upper Gulf of California remains full of life and continues to be a highly productive ecosystem. There are still plenty of fish for the vaquita to feed on ─ and the animals that were recovered showed no signs of malnourishment. If anything, vaquita have had more to eat since the gillnet ban was implemented as the measure has helped fish stocks recover from many years of over-fishing.

Then there is the suggestion that excessive habitat pollution is to blame for the vaquita’s decline. And to be fair, ocean pollution is a real threat and it affects many coastal marine mammal species in all our world’s oceans. Toxic substances like mercury, DDT, POPs and PCBs travel through the food web as smaller organisms like krill are eaten by larger organisms (e.g. fish). Because those pollutants do not easily degrade, they build up within these organisms over time (an effect called bioaccumulation). Predators at the top take in high concentrations of those pollutants whenever they consume prey (biomagnification).

Pollutants are stored within the fatty tissues of marine mammals (e.g. the blubber in porpoises) throughout their lives. Those chemicals can become dangerous if the animals go into starvation; that is when they begin to eat into their fat reserves and pollutants are metabolized and released into the bloodstream. We are still only just beginning to understand the effects; there is some evidence that it may compromise the immune system or lead to fertility issues.

However, a review of more than 150 studies found no signs of dangerous levels of contaminants in the Sea of Cortez. The vaquita are not starving and therefore not eating into their fat reserves; the animals examined showed no signs of a compromised immune defence and they are still reproducing. The only man-made thing that is killing the vaquita, and for which there is plenty of evidence, is entanglement in gillnets.

Broken Promises

Fishermen are feeling abandoned by the government ─ and they have a point. The government’s delayed response to the ecological disaster playing out in the Sea of Cortez has turned the local fishermen into antagonists. They are being portrayed as the bad actors. And the poachers do not deserve any better as their untethered greed has turned them into criminals with little regard for the ecologically rich habitat they are helping to destroy. But only a fraction of the fishermen belong into that category.

There are many honest fishermen who for generations have earned their living at sea, working long hours to feed their families. And when the fishing ban came into effect, the government failed to set them up for success. There are few opportunities to do anything other than fishing in a region where almost the entire economy depends on fishing.

When the government first announced a temporary ban on gillnet fishing, it promised and began to implement a range of measures to lessen the impact on the local fishing communities. Compensation payments were to make up for a loss of income, and an alternative fishing gear program was designed to give fishermen the ability to continue fishing ─ without gillnets.

But compensation payments were often criticized as insufficient to make up for the losses, and when the government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador took over in December 2018, reports indicated that payments had been halted altogether. In February 2019, the government announced a new agreement to compensate fishermen, but at least according to recent complaints on social media, payments have yet to be resumed.

A transition to alternative “vaquita-safe” fishing gear was recommended by CIRVA and multiple parties began to design solutions. Alternative gear has been tested in trials since 2013, but there are indications that some of the gear may actually be causing additional harm to the ecosystem. To this date, there is no fishing gear licensed by the responsible government agencies that could replace gillnets.

Among the fishermen, many are committed to saving the vaquita. They are part of the efforts to remove derelict and abandoned fishing gear from the Sea of Cortez, and they are involved in an acoustic monitoring program that helps estimate the number of vaquita remaining and their location. But there is still no sustainable long-term solution for them.

The Last Opportunity

The vaquita is running out of time. Help us save this beautiful species and its 6 cousins around the world.Help us Save the Vaquita

In its latest report, CIRVA calls on the government to “mobilize its enforcement assets to eliminate illegal fishing in the area where the last few vaquitas remain”. They suggest 24-hour surveillance and monitoring of the vaquita habitat, protection for the net removal teams ─ and they call for the arrest and prosecution of fishermen that violate the ban.

None of that is new; conservationists have been asking for those measures for years now. But the urgent tone of the CIRVA report conveys the desperation that has gripped the people who have dedicated their lives to saving the vaquita porpoise, the totoaba and the rich ecosystem that for millennia has sustained them both. They will need all the help they can get to avoid disaster.